Active travel: the state of play

The phrase ‘active travel’ is used to cover the ways in which people actively use streets: on foot, by cycling or using other wheeled modes of travel such as wheelchairs. It also includes electrically-assisted modes such as e-bikes and powered modes such as mobility scooters and e-scooters.

Since the 1950s, when the mass production of cars made them affordable to more people, most developed countries have designed their transport networks to prioritise car travel. This has, in turn, led to people travelling further for work and leisure, and to governments investing in infrastructure that encourages and enables car dependency.

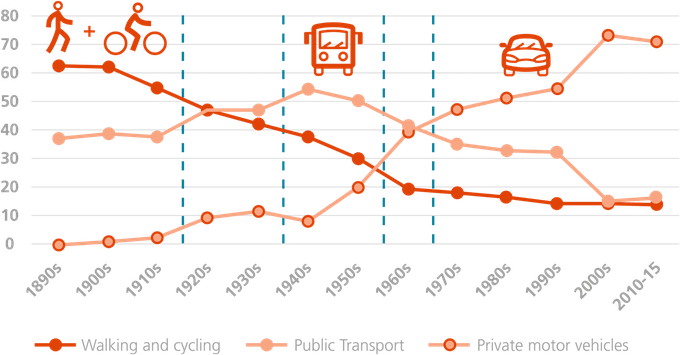

How commuting has changed

Journey to work modal choices in the UK (%)

Note: for the years 1890-1999, data was sourced from 12,439 journeys to work in 1,834 life histories, with statistics calculated for the decade in which a particular journey to work started (Pooley and Turnbull, 2000); the years 2002-15 use Department of Transport data (2017).

The consequences of prioritising car travel are evident in towns and cities, as well as in inter-urban settings: the most direct routes between destinations are often allocated to car travel, while people using public transport, as well as pedestrians, cyclists and wheelchair users, often have to take longer, non-linear, interrupted routes to get to the same place.

A short history of traffic engineering

Road usage and journeys

Source: Civic Engineers

In urban areas there can also be huge disparities between the amount of road space allocated to each mode (such as walking, cycling or driving) and the number of people who travel by that mode. On a busy shopping street, for example, some 75% of users could be pedestrians but they are often confined to narrow pavements that take up only 20% of the space.

Outside cities, new housing developments are often built with car travel being virtually the only way to get to nearby schools, workplaces, shops and leisure facilities.

The amount of government money allocated to each mode emphasises this disparity. In England, for example, planned annual government investment in the strategic road network (trunk roads and motorways) for 2020-21 equated to £84 per person (outside of London), compared with £8 per person on active travel measures. The disparity is slightly smaller in Wales, where £22 per person is allocated to active travel, and in Scotland (£21).

The need for change

Copenhagen has been ranked one of the world's most bike-friendly cities

Governments globally are looking at ways to reverse some of the problems caused by decades of prioritising car travel. In its 2020 report Gear Change: A Bold Vision for Cycling and Walking, the UK government highlighted the benefits to society of reducing car journeys and increasing active travel. These include improving air quality, combating climate change, improving health and wellbeing, addressing inequalities and tackling road congestion.

Copenhagen’s bicycle strategy, Good, Better, Best, takes the same view. “A bicycle-friendly city is a city with more space, less noise, cleaner air, healthier citizens and a better economy,” it says. “It’s a city that is a nicer place to be in and where individuals have a higher quality of life. Bicycle traffic is therefore not a singular goal but rather an effective tool to use when creating a liveable city with space for diversity and development.”

Active travel campaign group and infrastructure provider Sustrans says walking and cycling also contribute to economic performance through direct job creation and by supporting local businesses and the leisure and tourism industry.

How do we achieve more active travel?

The default design for many transportation engineers tends to centre around vehicles. But Hertfordshire County Council project manager Michael Melnyczuk thinks engineers need to start thinking differently.

“For highway engineers, the design focus is on vehicles without understanding end-user behaviour," he says. “They think about how many vehicles you can fit into a space but forget there’s a human element. If we are really going to enable active travel in the built environment, we have to understand that it’s about people travelling through the space and think about things on a human scale.”

Changing the question

Prioritising active travel over car use

Source: Guardian, Copenhagenize your city, 11 Jun 2018

Susan Claris, associate director, Arup, adds: “Transport is fundamental to the quality of life experienced in towns and cities, but for the past century the car has dominated how we plan and grow our urban areas. We need to place people back at the heart of our cities and drive a human-centred approach to the design of the built environment. And we must make sure that this human-centred approach includes all people – we must not design for an ‘average’ that does not exist.”

In a ‘One year on’ review of the Gear Change report, then prime minister Boris Johnson said: “Of course, some journeys by car are essential, but traffic is not a force of nature. It is a product of people’s choices. If you make it easier and safer to walk and cycle, more people choose to walk and cycle instead of driving, and the traffic falls overall.”

For cycling and walking to be attractive, routes must be direct and continuous – not disappearing at difficult places. They must also serve the places people want to go and the journeys they want to make. As Gear Change says: “If it is necessary to reallocate road space from parking or motoring to achieve this, it should be done.”

The Copenhagen strategy document says: “The central idea regarding infrastructure is thinking about a coherent, high-quality network without weak links in the chain. Just one intersection that doesn’t feel safe is enough for the elderly to leave the bicycle at home. Stretches without cycle tracks are enough for parents to not let their children cycle to school.” This is equally true for walking routes.

Active travel design principles

Cycling on London’s Blackfriars Bridge rose by 55% in the six months after a protected bike track was installed

The UK government is particularly keen to see people shift from cars to walking or cycling for shorter journeys. In 2018, some 58% of car journeys in England were under five miles, and in urban areas more than 40% of journeys were under two miles. Many of these could be made on foot or by cycling or another wheeled mode if the transport infrastructure made it more attractive, safer and easier.

Cycling on London’s Blackfriars Bridge rose by 55% in the six months after a protected bike track was installed. In peak hours, the route is used by an average of 26 cyclists per minute and, although it takes up only about 20% per cent of the road space, it carries 70% of all traffic on the bridge.

UK local authorities are responsible for setting design standards for roads. However, the Government has produced guidance and good practice for the design of cycle infrastructure, in the form of Local Transport Note 1/20 (LTN 1/20): Cycle Infrastructure Design for England and Northern Ireland, Cycling by Design published by Transport Scotland, and Active Travel Guidance published by the Welsh government.

LTN 1/20 identifies five core design principles that are essential to getting more people travelling by cycle or on foot, based on best practice both internationally and across the UK. Networks and routes should be:

- Coherent

- Direct

- Safe

- Comfortable

- Attractive

It also says that inclusive design and accessibility should run through all five of these core design principles.

Improving inclusivity and accessibility

Private car ownership is high throughout most of the world: for example, 91.3% of US households have access to at least one vehicle, 78% do in the UK and 95.7% do in Dubai. But a transport network that prioritises car travel ignores the needs of people who do not have access to a car or are unable to drive. It can even create or exacerbate inequities in society.

Although 78% of people in the UK have access to a car, the numbers are heavily skewed towards higher-income groups. Government statistics for 2018 showed that only 35% of people with the lowest incomes had access to a car, compared with more than 90% of those with the highest earnings. Fewer than half of those renting their homes from local authorities or registered social landlords had access to a car.

Transport policies in most developed countries effectively give greater value to people in cars – especially those who drive to work – than to people in other groups, such as those on lower incomes, parents with pushchairs, and users of mobility scooters, cycles and public transport.

As Jonathan Flower, researcher at the Centre for Transport and Society, University of the West of England Bristol, says: “‘Choice, choice, choice’ has become a modern mantra, but what choices exist for wheelchair or mobility scooter users when dropped kerbs at level crossings are missing; or for 12-year-olds to cycle alone when the only option is to share the carriageway with four lanes of fast-moving traffic; or [for a person] to push a double buggy when the footways are narrow; or [for a visually impaired person] to walk if routes are cluttered or blocked?”

He adds: “As planners, we talk about a user hierarchy of design, with pedestrians at the top and the motor vehicles that can cause the greatest harm at the bottom, but too often we only pay lip service to this, and the reality is that most streets are still car-dominated, with the driver at the top and pedestrians and cyclists at the bottom. If choice, inclusion and diversity have value, then this must change.”

New changes to the Highway Code have introduced a hierarchy of road users, with pedestrians at the top, followed by cyclists, motorcyclists, car drivers, van drivers and heavy goods vehicle drivers, with the aim of improving safety for those users at most risk from the actions of others.

Summary of changes to Highway Code

January 2022

Case study 1: the Netherlands

Some 27% of journeys in the Netherlands are made by bicycle

Cycling and walking account for 47% of all trips made in the Netherlands, with 27% of journeys made by bicycle (compared with 2% in the UK). It is easy to assume, therefore, that active travel – and particularly cycling – has long been part of the Dutch psyche. But this is not the case – the popularity of active travel is the result of a shift in policy to fund cycling infrastructure and make urban areas more ‘liveable’.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, the Dutch were just as car-focused as other developed nations and its transport networks were designed to prioritise car travel. However, concern about pollution and rising death rates led to public demand for safer roads, and towns and cities began introducing measures to make their streets more cycle-friendly.

Design for ‘liveable streets’ focuses on neighbourhoods, making the daily school run and local shopping safe and easy by walking or bike. Infrastructure supports this: there are 35,000km of dedicated cycle paths in the Netherlands, and cycling between small cities is common, with easy connections to big cities. Junctions and roundabouts often include tunnels or different routes for bikes, and there is no route sharing with pedestrians.

Arcadis UK technical director Keri Stewart and Netherlands project leader Marloes Scholman say other countries should not ‘copy and paste’ the Dutch experience, but learn from the country’s approach: “If you understand what you would like your neighbourhoods to be, you start to look at towns and cities through a different lens. Examine the role of each street and begin decision-making based on those functions. Look at different routes and understand the point of them. Look at how to make schools and shops accessible.”

They say it is critical to engage with communities from the outset: “If residents buy into the vision from the start, each development and change is understood as part of an overarching plan. Behaviour change starts with winning hearts and minds, so celebrate success, and rather than castigating people who continue to rely on cars, make it easy for them to switch through a whole-package approach. A focus on local areas ensures schools, shops, hospitals and employment areas have the supporting infrastructure built in.”

Case study 2: Glasgow Avenues and

Places for Everyone

Artist's impression of changes to Cambridge Street as part of the Glasgow Avenues scheme to boost active travel

Glasgow Avenues

The £115m Glasgow Avenues investment programme is transforming the city centre’s streetscape and public realm, making it more people-friendly, attractive, greener, sustainable and economically competitive.

The programme will reshape 21 streets and adjacent areas to prioritise space for active travel, boost connectivity, introduce sustainable green infrastructure and improve the way in which public transport is accommodated. It takes in some of the city’s best-known thoroughfares, including Argyle Street, Great Western Road and Sauchiehall Street.

Funding came from the Glasgow City Region City Deal. Work started in 2018 with the Sauchiehall Street ‘pilot’ Avenue, which was completed in 2019. The rest of the work will be phased between now and 2028.

Since the scheme started, Glasgow City Council has secured a further £21m from Sustrans, which will enable four more Avenue projects to be delivered, enabling the council to accelerate and expand the programme into other areas of the city.

Places for Everyone

Places for Everyone is a £2m collaboration between the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow City Council, City of Glasgow College and Sustrans. The aim is to form an active, safe and walkable Learning Quarter in the north-east of the city centre by creating an urban realm that improves the physical environment and allows students to move freely between the university, college, Glasgow Caledonian University and the rest of the city centre. The project will also create cleaner, safer, pedestrian- and cycle-friendly streets.

The whole area will be redesigned so that it functions first and foremost for pedestrians – which will be achieved by reducing barriers to movements and improving connections between origins and destinations. Consultancy Stantec says the design of this ‘people-first’ environment can act as an exemplar of how to change city-centre space to reflect the needs of walkers and cyclists.

The first phase of the project is a plan to pedestrianise and re-landscape three streets that are home to some of the University of Strathclyde’s main buildings. The ‘Heart of the Campus’ project will transform the area into an accessible set of spaces, with inclusion a priority.

Case study 3: Connswater Community Greenway, Belfast

Cyclists pass through Victoria Park during the annual Ride on Belfast event (credit: nigreenways)

Connswater Community Greenway is an urban regeneration project that is transforming East Belfast by combining improved flood protection with the creation of public spaces and pedestrian/cycle routes that connect communities.

The £40m project is being delivered by Belfast City Council in collaboration with local regeneration organisation EastSide Partnership. Another key participant is Northern Ireland’s rivers agency, DfI Rivers, which is delivering flood alleviation measures for homes and businesses within the catchments of the Connswater, Knock and Loop rivers via a project that offers wider community benefits.

The physical elements of Connswater Community Greenway support community cohesion and interactivity, economic development, improvements in public health, cleaner rivers and greater flood resilience. What could have been delivered as a standalone flood alleviation scheme and a separate urban regeneration programme have been combined to become an award-winning project with positive and lasting benefits.

One of the most visible features is a new 9km linear park linking existing green and open spaces and allowing residents to travel across the city easily via car-free corridors. The project includes 16km of foot and cycle paths and 26 new or improved bridges and crossings.

Case study 4: CYCLOPs junctions, Manchester

The UK’s first CYCLOPS (Cycle Optimised Protected Signals) junction in Hulme, Manchester

The UK’s first Cycle Optimised Protected Signals (CYCLOPS) junctions have been established in Manchester, using a design that separates pedestrians and cyclists from traffic, reducing the risk of collisions or conflict and enabling pedestrians to get to where they want to be in fewer stages with more space to wait than on other junction designs.

The first CYCLOPS junction was installed in 2020 as part of the Manchester to Chorlton cycling and walking route. It is intended to act as a blueprint for future junctions as part of Greater Manchester’s Bee Network, 2,880km of joined-up walking and cycling routes that will connect every community across the city region. More than 30 more CYCLOPS junctions are in development across Greater Manchester, and the approach has been adopted elsewhere in the UK and in Ottawa, Canada.

The junction was designed by Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM)’s traffic engineers and walking and cycling team, in response to some of the flaws in existing UK junction designs.

TfGM engineers Richard Butler and Jonathan Salter say: “The main difference between this junction and traditional UK junction designs is that cyclists are offered an alternative safer route around the junction. They are no longer required to position themselves on the nearside of the lane, allowing vehicles to pass on their offside which is often the cause of so-called ‘left-hook’ incidents, where cyclists going ahead are struck by a vehicle turning left from the same lane.

“The CYCLOPS resolves this with its ‘external orbital cycle route’ which separates cyclists from motor traffic. Bicycles approaching from all four ‘arms’ can use the cycle track, which encircles the junction to make left, ahead and right turning movements, safely protected from traffic.”

Developing active travel infrastructure

Those developing active travel infrastructure need to understand the barriers preventing people from walking or cycling

Key steps involved in developing infrastructure for active travel include:

- Creating a clear vision for liveable places with provision for increasing cycling and walking

- Engaging with communities from the outset

- Understanding the barriers that prevent people from walking and cycling

- Securing political backing

- Creating safe and reliable routes to destinations – not detours

- Adopting best practice from other countries

- Understanding the wider benefits of active travel, such as improved health and wellbeing, reduced inequality and gains for the economy

Sign up to receive news from ICE Knowledge direct to your inbox.